Director: William Wyler

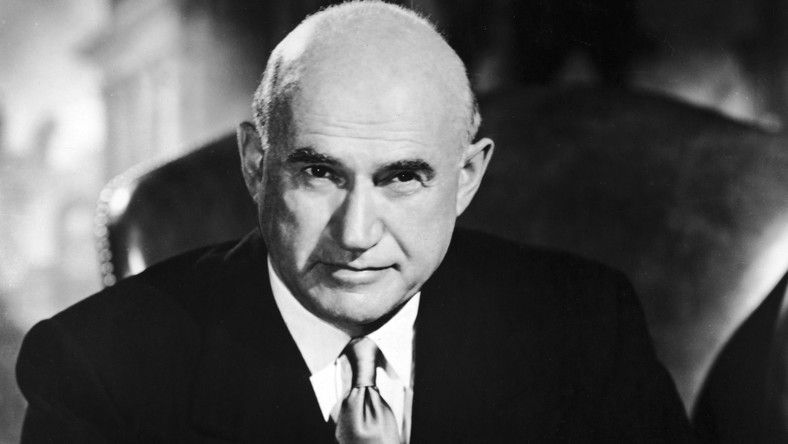

Producer: Samuel Goldwyn and Merritt Hulbert

Production Company: Samuel Goldwyn Productions

Distributed by: United Artists

Screenplay: Sidney Howard

Adapted from the 1934 play by Sidney Howard and the 1929 novel by Sinclair Lewis

Cinematography: Rudolph Maté

Original Score: Alfred Newman

Editor: Daniel Mandell

Production Design/Art Direction: Richard Day

Meanwhile, Ruth Chatterton is phenomenal. In 1936, she was forty-four, and her popularity was in decline. Her character is too close to the bone for comfort. In fact, I’m not sure if any movie or actress has captured the dread of aging with such power and precision.

I consider myself to be a 1939 man. For me, that is the year the movies began in earnest. Although Hollywood had started to emerge as the center of the universe as early as 1913, and films had been made in New York/New Jersey, as well as in France and Italy, for an entire decade before that. I have no affinity for silent films, which I consider a completely different art form. And many of the talking motion pictures made before 1939 seem just as alien to me. It’s like comparing Greta Garbo, whom I find hopelessly unappealing, and Ingrid Bergman, one of my favorite actresses. In fact, there are only two pre-1939 Hollywood movies that I would list among my all-time favorites. One of the best Astaire/Rogers RKO movies is Mark Sandrich’s “Top Hat” from 1935. The other is Samuel Goldwyn’s production of Sinclair Lewis’ (by way of Sidney Howard) “Dodsworth”, William Wyler’s 1936 masterpiece.

Swiss-German-American film director William Wyler immigrated to the United States in 1921. At the tender age of nineteen, he left his native Alsace (now part of France but then part of Germany) for California thanks to being a distant relative of “Uncle” Carl Laemmle, the founder and head of Universal Studios.

Becoming a director in the mid-twenties, he did little of note until he joined forces with Samuel Goldwyn in the mid-thirties. “Dodsworth” was their second production together following “These Three,” an adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s “The Children’s Hour”. They had changed Hellman’s story from gay to straight, thus creating the perceived triangle of Miriam Hopkins, Merle Oberon, and Joel McCrea. The two movies launched Wyler as a major director, and with “Dodsworth,” he received the first of his record 12 Academy Award nominations for Best Director. Martin Scorsese currently has 10 nominations and Steven Spielberg has nine. Billy Wilder has eight, while Woody Allen, David Lean and Fred Zinnemann have seven.

Sam Dodsworth (Walter Huston), a “self-made man,” is resigning from Dodsworth Motors, the company he founded twenty years earlier. His only retirement plan is an extended European vacation with his wife, Fran (Ruth Chatterton).

While traveling on the Queen Mary to England, Sam meets Edith (Mary Astor), an American divorcee living in Italy. At the same time, Fran flirts with a young Englishman (David Niven) before getting cold feet. They decide to skip England in favor of Paris, but not before Sam and Edith promise to stay connected and exchange addresses. Desperate to lead a high-class social life, Fran shaves years off her age. She and Sam gradually grow apart, and she begins a series of affairs with younger men, one of whom (Paul Lukas) is a notorious playboy.

She eventually asks Sam for a divorce to marry the boyish Baron Kurt von Obersdorf (Gregory Gayle). However, when Kurt’s mother (Maria Ouspenskaya, in a devastating scene) rejects his request to marry because Fran is too old to bear him children, Fran has no choice except to return to Sam and the United States. But it’s too late. Sam has been in contact with and fallen in love with Edith. The last scene in the film is a close-up of the smile on Edith’s face as Sam arrives at her home in Venice, Italy.

Sidney Howard, who would adapt “Gone with the Wind” for the screen two years later, did a superb adaptation of his own stage play. It comes in at an economical 101 minutes. In addition, Wyler does an excellent job, getting three of the best performances in American cinema up to that point in time. Performances that seem as fresh and vibrant today as they did then.

Huston is utterly believable as the displaced American. However, as sometimes happens in a Wyler movie, the film belongs to the ladies. Mary Astor, playing a character a little older than she was at the time, delivers a beautiful, understated performance, one of the best of her lengthy career. Meanwhile, Ruth Chatterton is phenomenal. In 1936, she was forty-four, and her popularity was in decline. Her character is too close to the bone for comfort. In fact, I’m not sure if any movie or actress has captured the dread of aging with such power and precision.

.

Unfortunately, when the picture received its seven Oscar nominations, neither Chatterton’s nor Astor‘s names were on the list. Astor continued a long and varied career (including an Oscar for supporting Bette Davis in “The Great Lie,” 1941) until retiring in 1964. Chatterton made only two more films before retiring from the movies in 1938.

DODSWORTH IS AVAILABLE FOR STREAMING ON AMAZON PRIME VIDEO, APPLE TV+, YOUTUBE

https://thebrownees.net/the-great-cinematographers-of-hollywoods-golden-age/

https://thebrownees.net/the-42-most-honored-directors-in-cinema-history/

https://thebrownees.net/the-childrens-hour-1961-film-review/